March 7, 2019

A few facts

The concept of building a canal to join the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean began with the Spanish in the 16th Century. They wanted to build a canal through Nicaragua, but that plan never panned out.

The French picked up the effort in 1880 when they began to build a sea-level canal in Colombia in the area now known as the Panama Canal. Unfortunately for the French, they ran out of money and 25,000 workers died, primarily from diseases.

The US was ready to pick up where the French left off (purchasing their land rights for $40 million), but Colombia was not in favor of the idea. For a time, the US pursued a plan to build a canal in Nicaragua (like the Spanish) but soon focused back on the Isthmus.

Since Colombia wasn’t in favor, lobbying by the US led by Theodore Roosevelt (plus some mighty military presence) and financial backing by a wealthy French financier (he still had his fingers in the canal deal and would lose his shirt if it fell through) allowed for a successful (and bloodless) revolution creating the Republic of Panama and securing the right to build the canal.

Although the original plan was to build a sea-level canal, it proved to be impossible due to the terrain. Attention changed to a lock-controlled canal that would allow ships to transit up over the land to get to the other side. Progress was slow. The fact people were dying from tropical diseases limited the number of people willing to work on the project. That was until William Gorgas connected the medical dots between mosquitoes and the transmission of disease.

Screening for windows and doors, pesticides to control bug reproduction, and eradication of standing water in populated areas boosted morale and lessened the numbers of graves dug. During the US canal build, only 5,609 people died due to accidents or disease.

On April 1, 1914, the canal was completed. It was officially opened on August 15, 1914, with the transit of the SS Ancon. The Canal Zone remained a territory of the US until 1977 when the territorial control began to transfer to Panama. The process was completed on December 31, 1999.

These days, vessels are built wider, longer and taller; therefore, a new lock system was created by the Panamanian Government to accommodate the new mega ships. It was finished in 2016 and uses a different type of gate (rolls in and out) and a new system for water storage to not deplete the water reserves of Gatun and Miraflores Lakes.

- Total cost of the original Panama Canal to the US: $375,000,000

- Total number of workers during the US build: 75,000

- Total amount of excavated material: 238,845,582 cub yd (US); 268,000,000 cub yd (French)

- Number of ships to pass in a year: 13,000 to 14,000 (avg 30-40 per day)

- Time it takes to pass through the canal: 8-10 hours on average

- Price for the Nieuw Amsterdam to pass through the canal: $450,000 + $35,000 reservation fee (estimate)

- Most paid by a vessel to transit the new lock system: approx. $1.2 million + a reservation fee

- Income to Panama generated by the Canal: $2 billion per year.

Our day

The When & Where delivered to our stateroom last night advised our estimated time of approach to the first set of locks was 8:00 a.m. They anticipated we would pass by the city of Cristobal, the start to the whole process, around 6:30 a.m.

We were up at 5:00 a.m. and the third/fourth persons in line at the bow opening on Level 7 at 5:30 a.m. The crew opened the door at 5:55. Joan and I were through the door immediately, positioning ourselves front row center at the railing. We had an unobstructed view of everything if it hadn’t still been pitch black. We stood in this very same spot, happily, for the next 4 1/2 hours.

As the sun came up over the horizon, we saw the first set of locks in the distance. As we glided closer and closer, more and more people spilled onto the bow decks below us.

Whereas we were located on the smallest of the decks with the fewest amount of spectators, the main bow deck on 5 was filled with rows and rows of people jockeying for the right to get that first glimpse of the canal opening. Of course, they handed out coffee and creme filled Panamanian pastries on deck 5, so that also added to its popularity. As much as we begged, no one attempted to throw any of the pastries up our way ~ we got o taste one. That’s OK, we had what we think was the best view.

As we slipped into position in our lane of the canal, we watched as a large tanker in the opposite lane was lowered in three steps down the 85 feet from the level of Gatun Lake to the Atlantic Ocean/Caribbean Sea. Gatun Lake was actually created by flooding the valley ~ the islands seen in the lake are the tops of hills and mountains.

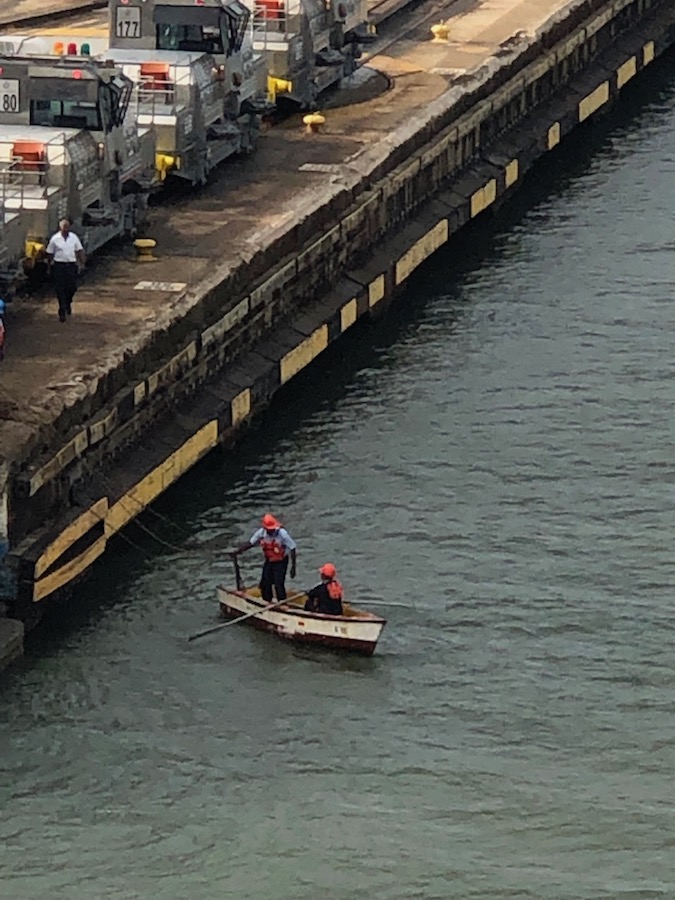

As we closed the gap to the first lock, we saw a small rowboat with two men in it approach the front of our ship. These men received the lines thrown down from the ship. They threw them up onto land to be attached to the mules. The cars keep the lines taut so the ship maintains its center in the lock. After all, at 106 feet wide, there was only two feet on either side between the ship’s hull and the wall of the lock.

Although it sounds dangerous to have men in a rowboat, they’ve tried other methods of getting the lines from ship to shore, such as a gun. They found the human touch to be far more accurate. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

The first set of gates finally opened. We slid into the lock.

The gates re-secured behind us, the lock filled with water from below. No pumps are used, only gravity. It’s a fascinating process. They say it takes close to a million bathtubs of water to fill a lock. That’s a lot of water.

The ship rose higher and higher. Suddenly we were at the water level of the next lock. The second set of gates opened and we entered the next lock and the process was repeated … and then again a third time.

While we rose on our side, other vessels were lowered on the other side. As ships passed we waved to them, they waved back. We took pictures of them, they took pictures of us. Everyone was thrilled to have such an awesome experience. It really is an engineering marvel.

And suddenly, we were through the Gatun Locks and raised up the 85 feet to Gatun Lake.

The landscape is beautiful, each island a tropical rain forest and uninhabited. The lake is huge ~ it would take 600 billion bathtubs of water to fill it. It takes approximately two hours to cross to get to the next lock.

Knowing we had a long crossing, and since we had missed breakfast (including the Panamanian pastries), we finally gave up our premier viewing spot and went to lunch.

Afterward, we gathered our things (book, iPad, iPhone camera). We looked for seats in the Crow’s Nest (11th deck) to take in the transit through the Culebra Cut – the narrowest part of the canal. The competition among fellow passengers, particularly ones who started happy hour early, for prime seats was not for the faint of heart.

Just before we got to the Pedro Miguel Lock (only one lock) to start our journey back down to sea level, we passed through the Continental Divide. We saw the small prison where Manuel Noriega was held until he got sick in 2017 and then died.

Photos were difficult to take through the glass of the Crow’s Nest and several people were jockeying for positions at the windows. So, Joan and I returned to our place at the rail on the bow of the 7th deck for the final locks. The two locks of the Miraflores Locks would lower us approximately 26 feet each back down to sea level.

As we came closer to Miraflores, we saw a large tanker, several sailboats, and some tugs lowered in the lane next to ours. (Small boats share a lock with other vessels so the fees can be shared). We also saw the multi-level tourist center built to educate people about the Canal. From here, they can watch the transit of ships through the two locks ($15 entrance fee for non-Panamanians, $5 for locals).

They waved at us, we waved at them as we were gracefully lowered back to sea level (the Pacific Ocean is actually 40 cm higher than the Atlantic Ocean). It was awesome to see the gates open and shut with such ease for the final time. The gates weigh up to 750 tons each and are still the same ones used 105 years ago when the Canal opened.

Approximately 8 1/2 hours after we reached the first lock, we exited the final lock and glided into the Pacific Ocean.

The entire day was fascinating, thrilling, and exhausting, but it was perhaps one of the coolest experiences in my life. Would I do it again? In a heartbeat. Do I recommend that you do it (if you haven’t already)? Absolutely!