August 15, 2019

I had set aside today to travel out to Malbork Castle, the largest brick castle in the world; that was until I found out it was a double-holiday. Not only was it a holiday honoring the Virgin Mary, but it was also Armed Forces Day. What that meant was that everyone had the day off and was traveling around. The anticipated crowds on the trains and at the castle were staggering. I decided to leave it for a future trip.

After getting some work done, I gathered my strength and joined the crowds milling around the streets for St. Dominic’s Fair (it ends this Sunday).

I focused my energy on getting to the … Hungarian twisty bread stand. I just had to have another.

The crowds were dense, but I made it to the main street only to find it was closed in sections due to a marathon. I always seem to find a marathon.

It took time, but I finally made it to the Golden Gate to meet the guide for yet another Walkative free tour. Although not the topic of the tour, our wonderful guide Filip started off by talking about the rebuilding of Gdansk after the war.

Since the entire town was in ruins and the Soviet Union/Communists were in charge, the major thought at the time was to scrap everything and build a new modern city in its place. There was another opinion, however, that the main/old city should be rebuilt to its former glory to maintain the history and spirit of the city, but with more modern facilities. This way, the people would continue to be happy while the government controlled how things were built. So, they blended the past and present – building a new city with a historical façade.

While many of the buildings look like individual houses from the front (as they were in the past), they aren’t. Behind the façade, there are apartment houses built for the workers of that era that use multiple “house fronts” as their faces. I was a little disappointed to find out that much of the beautiful architecture were false fronts, but it doesn’t lessen the beauty. What is old is new again.

Filip also talked to us about how the communist party controlled society from the inside. The political police/secret service (SB) had agents undercover within the working class to monitor what people did and said. In the 1970s, they estimate there were 25,000 agents undercover. Additionally, the SB had 90,000 secret collaborators – people who weren’t agents but were paid to snitch on their friends, relatives, and co-workers. The result was that no one spoke openly and no one acted out of line – it’s the way they divided society, operating on fear.

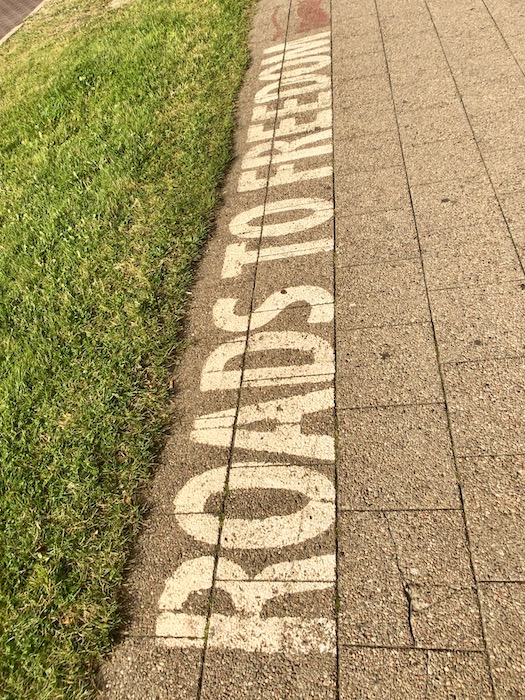

It is with this backdrop that we come to the actual topic of today’s tour – Solidarity, the movement of the workers in the 1970s and 1980s that eventually led to the demise of communism in Poland and elsewhere around the world.

After the hope of a better tomorrow held out by the communists in the late 1940s/early 1950s (anything had to be better than post-war hunger and strife), the desire for freedom began bubbling to the surface. The ideologies of the new generation, those born during and after WWII, didn’t line up with the current regime. Since Gdansk was a port city, sailors would dock and bring with them news and products from around the world. One of those “products” was music – rock & roll music. To this generation, R&R (called Big Beat in Poland) meant freedom of thought; they didn’t care about the language of fear governing their elders. In 1959, the first Big Beat concert was played at the Ginger Cat to a welcoming crowd. It was just the beginning.

Time went on, there were strikes here and there, but in December 1970, just before the holidays, the communist party raised prices of goods/consumables 20-25% across the board. This action caused massive unhappiness. The workers at the Lenin shipyard went on strike. There was a ripple effect through the city and pretty soon many trades were on strike all at once. The government didn’t react – more people went on strike and within two days, the entire coast of Poland was on strike. Still, no reaction by the government, so striking workers burned the party building.

The army was mobilized, storming the city and shooting people on sight. The number of casualties is unknown, but within three days order was restored and the strikes were busted. Many lost their jobs and/or were imprisoned – including Lech Walesa (a former shipyard electrician). A memorial stands in Solidarity Square honoring those killed in the 1970s strikes. The anchors in the monument are symbolic of hope and the circles running from the base of the monument symbolize a ripple effect.

Even though the strikes were squashed in 1970, people begin to realize that they needed to take action. The underground was very active and waited for an opportunity to act.

As with most good stories and big battles, the strike to end all strikes started with a woman.

Anna Valentinovitch aka Mamma was a beloved worker at the Lenin Shipyard. She had worked there since 1950 and had survived the 1970 strike, but she was vocal. She was very popular with the workers because she was known to help everyone, including those within the opposition. Several times, she and her family were the subjects of SB investigations and interrogations. In August 1980, six months before retirement with full benefits, she was summarily discharged from her duties without the possibility to obtain any benefits. It was the party’s way of showing the workers what could happen to those who assisted the opposition.

Enough was enough. By mid-morning on August 14, 1980, the news of Anna’s discharge had spread through the shipyard. Within three hours, a strike had been organized demanding her reinstatement. To mitigate the damage, the shipyard’s CEO sent a limo to pick Anna up and had her reinstated. But this wasn’t enough. By this time, Lech Walesa, a former shipyard worker, and leader had jumped the wall surrounding the shipyard and had rallied the strikers to demand more. He also advised that they should not take the cause to the streets but that they should stage an occupational strike.

Rumors of the Lenin shipyard strike spread like wildfire before the party could terminate outside communications. Various other shipyards up and down the coast joined the movement organizing occupational strikes. The strikes spread to other groups such as the mines and railroads. Within two weeks, 724 facilities and a million workers were on strike. By this point, the movement had spread too far; the party had no hope of using force to control the situation. The country stood at the point of collapse. The party had to talk with the strikers.

What began as 2,000 demands from the various striking groups was boiled down to 21 demands from the National Striking Committee. A copy of the demands is situated above the gate at the Lenin Shipyard. It would become one of the most important documents in history. The demands were not just for the striking workers but were to be applied to all Polish workers – the most important of which was the development of independent trade unions. This alone decimated the cornerstone of communist ideology.

On August 31, 1980, documents were signed with Lech Walesa as a primary signatory.

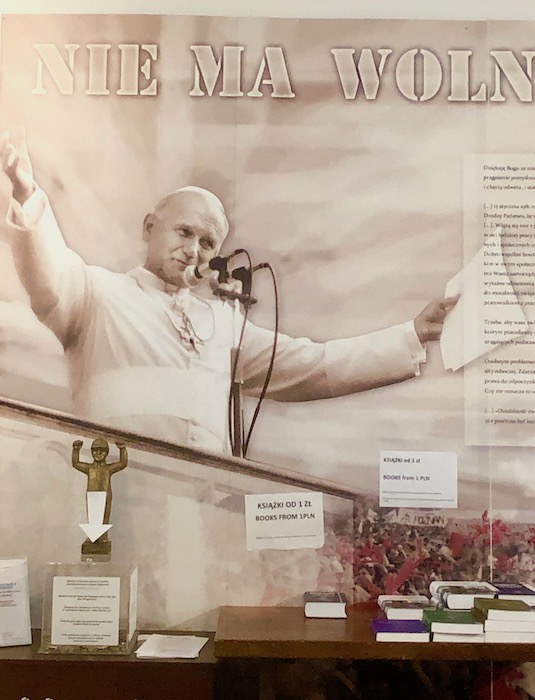

Solidarity lasted 15 months until the party instituted Marshall Law. But, it was too late for the party, society was behind solidarity. Even the church, very important to the Polish people, supported solidarity. Pope John Paul II famously said, “There is no freedom without Solidarity.”

Marshall Law actually accelerated the demise of the party. In 1989, the party accepted Solidarity as a legal party, and the rest is history. A domino or ripple effect was felt throughout the world.

Filip was an awesome guide on our walk through the solidarity movement. He was so passionate about the subject matter and you could feel that he had so much more to say beyond the 2½ hour tour. I learned so much from him and he made the learning environment fun and engaging. What started as just an add-on tour became one of my favorite walking tours during my trip thus far.

It was well past dinnertime when I left the museum at the shipyard. With my sights set on one of the food vendors close to my apartment, I made my way through the back roads of the old town. The first food vendor I approached was just closing up (no it wasn’t the Hungarian twisty dough vendor), but I was able to snag kielbasa, potatoes, and garden vegetables at another. It was a pretty good meal, although the sausage was too much to finish. After all, I had to save room for a little ice cream – when in Poland, do as the Polish do, right?

I spent the remainder of daylight on my last official night in Gdansk sitting under the shadow of a church steeple watching children play and giggle in and around a dancing fountain. In any language, there’s nothing more infectious than children’s laughter.

It was a “feel good” evening. Goodnight gorgeous Gdansk, until we meet again.