August 11, 2019

Of all the free walking tours I’ve done on my trip, the most impactful was today’s tour through Jewish Warsaw. I’m sure that the phenomenal guiding skills and vast knowledge of our Walkative tour guide Batosz had a lot to do with it. He was so passionate about the topic and was so engaging that the entire group hung on his every word. But, it was also the subject matter. To understand that the entire area was destroyed and left in ruin with none of the 400,000 Jews who previously lived in Warsaw remaining after the war was horrifying, haunting, and humbling.

To get to the starting point of the tour, I had to walk past the Palace of Culture and Science, the tallest building in Poland. Built in 1955, it is a building mired in controversy. Many people, including the current President, want the building destroyed saying that it is a constant reminder of Soviet domination over Poland. Others say that it represents the city’s ability to rise again from the rubble created by the war. It will be interesting to see who wins the debate.

The tour started at All Saints Church, whose interior is undergoing major restoration. A statue of Pope John Paul II stands on the steps welcoming parishioners. The area around the church is what makes it significant in the story of Jewish Warsaw because it was the beginning of the end for so many. Although earlier in Warsaw’s history it was an area where Jews and Christians were integrated and lived amicably, it was here that thousands gathered voluntarily during “resettlement” with the promise of extra food rations and a new life only to be packed into cars and taken to gas chambers in the forest of Treblinka. What a way to start the tour.

Our first official stop on the tour was a brightly colored mural on a wall close to the Orthodox Synagogue. It depicts a train carrying two giraffes, a bear, and an elephant. The steam cloud from the locomotive carries within it portions of the poem written in the early 20th century by Julian Tuwim, a Polish (Jewish) poet. It is a poem that school children still today learn by memory. I think we can liken it to the story of the little engine that could – possibly analogous of the of rebirth out the ashes of Warsaw (but that’s just my opinion).

The Orthodox Synagogue is the only synagogue in Warsaw that survived WWII. It was spared because it was a large building and the Nazis needed it to house … pigs. Not only was it convenient for them, but it was also another way to humiliate the Jews. We didn’t get a chance to go inside the synagogue – I’ll save it for another trip.

Today, there are six synagogues in Warsaw, with others in the planning stages. Although no Jews remained after the war, there are now 4,500 living and worshipping in Warsaw.

Walking further into the old Jewish ghetto area, we came across the largest piece of street art in Warsaw. One side of an old building is painted white with the word Kamienico painted in block letters and a red balloon rising above the letters.

When read literally, Kamienico means “tenement building,” which is exactly what the building on which the mural is placed was during the war. It was one of the excessively overcrowded tenements in the Jewish Ghetto. It’s what poet Wladyslaw Szlengel described about Jewish ghetto life in his poignant poem “Doorbells.” It’s a dilapidated, shell of a building. However, Kamienico when broken down also means “a stone and what?” In a time when people are quarreling over whether to tear the building down or let it stand, the phrase makes you ponder what it is beyond being just stones and mortar. It’s a symbol of the horrors of life, resettlement, and death that occurred, but isn’t it also a symbol of resilience and resistance since it still stands when so many buildings around it perished. It is not only a building; it is a piece of history that holds the heritage of a people, which deserves to be saved. But, again, that’s only my opinion.

And don’t get me started about my opinion on a new hotel going in across the street integrating one of the only remaining sections of the ghetto wall into its foundation.

Scattered on roadways, you come across markers in the pavement that indicate where the border walls of the ghetto were placed. I’d noticed one close to the Palace of Culture but didn’t realize what it was at the time.

There were actually two ghettos, split by Chiadna Street, which the Nazis believed was important for the transport of goods. Between the two ghettos and over the road, there was a bridge. Crossing the bridge was difficult for Jews, not physically, but emotionally. It was the only glimpse they had of the life they had before and would never have again. A monument now stands on each corner.

July 22nd is a date remembered in Warsaw by marches and remembrances – it is the date on which the resettlement of the Jewish Ghetto was to begin. At the time, Adam Czerniakow had been named by the Nazis as chairman of the Jewish Ghetto. He had been left with little means to manage the 65,000 people living in that small area. His diaries of ghetto life are disturbing. When presented with the order for the resettlement of the Jews, he read between the lines and knew he couldn’t sign such a death sentence. Instead, he committed suicide and his second in command was made to sign it and the order was carried out immediately. We made a stop in front of his house.

We also made a stop in front of a courthouse built before WWII that was used by the Nazis to carry out the agenda of the state. Jews who had objections about their living conditions were allowed to go before the courts, but because they technically had no rights in the eyes of the state, no one ever won. Through the lower level of the courthouse, escape from the ghetto could be made; however, since the person needed to blend in on the other side, he/she couldn’t take anything with them, so it was difficult to survive. Additionally, the Nazis rewarded anyone turning in a Jewish person outside the ghetto with food and money, so even if you escaped, you’d likely be turned in and then sentenced to death.

The only successful rescues from the ghetto were by the Polish resistance, who rescued 13,000 people from the Jewish ghettos in Warsaw. To save one person took 15 people who operated in secrecy. To blow their cover and kill not only the Jewish person but the 15 people who assisted, took only one person. If you helped a Jew, you and your entire family were sentenced to death.

The last stop on our tour was the monument to the Ghetto Uprising, located in the courtyard of the Museum of the History of Polish Jews. On the far side, is a relief of downtrodden individuals being moved during the resettlement. On the other side, is a bas relief of the leaders of the Uprising. Stories of what happened in Treblinka made their way back to the young people still living in the ghetto (the Nazis kept them to perform manual labor). An underground movement, supported by the resistance, decided to make the Nazis pay for what they had done in the forests. They knew they wouldn’t beat the Germans, but they were prepared to die fighting – they decided their destiny. In April 1943, a battle that was expected to only last two days, lasted four weeks. Survivors were taken and executed, and the ghetto was demolished. Only rubble remained.

Anything built in the ghetto after the war is built on top of the rubble. This is why much of the area is up to nine meters taller than the rest of Warsaw. The first thing that was built after WWII, was the monument to the ghetto uprising (1948).

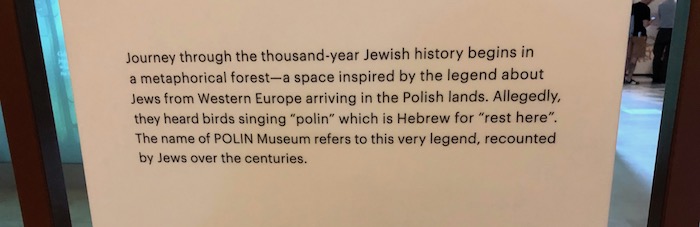

After the emotionally charged tour ended, I spent several hours in the Museum of the History of Polish Jews.

Mezuzah pulled from the rubble of the Jewish Ghetto post-WWII

It was an in-depth look at the entire history of the Jewish people in Poland from 966 forward. The museum is divided into sections and uses a multi-media approach to education. It is fascinating, but be prepared to spend a lot of time (and several bathroom breaks) to get through the entire museum.

My favorite section of the museum was “The Jewish Town,” which has a recreation of the gorgeous roof and bimah of the Gwozdziec synagogue, initially built in 1650. The wooden synagogue was destroyed by fire in 1914.

After such a heavy day of history, I spent the remaining hours wandering up one street and down another, ultimately coming to the main squares of the Old Town. Although 80% of Warsaw was destroyed during the war, the city has painstakingly recreated the Old Town to its prior glory. The architecture is awesome – the homes, the churches, the government buildings, the monuments, and the university.

For a Sunday, there was a lot of activity – there was a bicycle marathon, a protest, and lots of people milling around.

The main activity of children seemed to be chasing bubbles, and the overarching activity of everyone was eating ice cream (the Poles love ice cream). I even came across an impromptu piano recital and a pop-up book fair. Proof that life goes on.